Passion

'In a recent interview, Marc Andreessen [an investor who made all his money in tech and then VC investing] was asked what his best advice would be to a smart 23-year-old American today. "Don't follow your passion," he said. "Your passion is likely more dumb and useless than anything else. Your passion should be your hobby, not your work. Do it in your spare time."'

Business Insider - Jun 22, 2021

Don't follow your passions. Don't do that which brings you joy. At best, it's a frivolity. At worse, it's just taking up your spare time when you could be consuming more.

The Future of Art Making

I think a lot about what the future holds for us. Like you, I am concerned (to say the least) for the ever changing climate. I worry about the divisive and tense politics of our times. Wealth disparity, economic catastrophes, and the kind of indentured servitude many of us find ourselves in: the list goes on.

I sometimes imagine these post apocalyptic futures where the trappings of my own life are stripped away and, like so many others, we scrape the earth for sustenance, banding together in our little tribes, trying to fight our way through an inhospitable landscape. It's unlikely to come to that in my lifetime although that isn't to say it's not possible.

On Painting

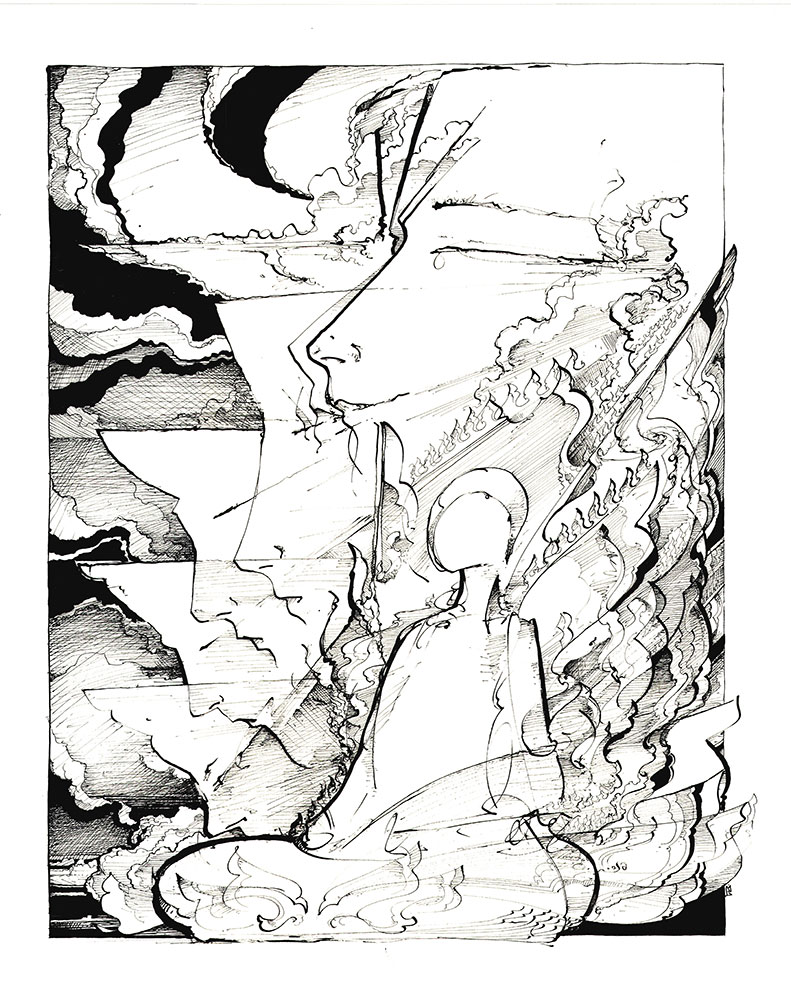

Sometimes, I'm painting and I'm just putting globs of paint onto the canvas, working it out as I go along blending it there rather than on my palate. I think to myself, "How could I really even begin to teach this? Who the hell wants to learn a process that can be so... messy!" It looks like a haphazard approach at times. The dollop of paint gets smeared onto the canvas along with several invisible dollops of faith in the process. All things considered, it usually works out, even when it doesn't. So how does one teach that? Well, I look at my whole approach then not just the smearing of the glob of paint on the canvas. I have a clear idea of what I'm doing from the start usually. In the exact instance that I'm speaking of, I was working on the kid's book that has been consuming all of my creative time. The kid's book has a certain style and approach that I've used from the very beginning. Regardless of new ideas I've had in the past three and a half years about layering or glazing, I can't apply them here because it would be inconsistent with the previous panels. I have to stick with the approach I've taken thus far in order to see it through. In some respects, this is a good bit of discipline. In the midst of this book that I've been working on for over three years, I've painted two great paintings and a handful of smaller but still important pieces. Those paintings have allowed me to express for a bit those thoughts and understandings about process - especially The Glass Onion with all of it's underpainting and layering and such.

And then I come back to this image and right now there is a blue sky backdrop to grandly rolling clouds, a floating cliff topped with a buzz cut of green grass, and two people. I paint a field of blue. I throw on the green. I do this, I do that. But what is the approach, really?

How To Be a Painter Part Something or Other

1. Sleep when you are tired. Naps are perfectly acceptable.

2. Eat when you are hungry. Eat good food, just not too much.

Relativity

Near. Far. High. Low. Sunrise. Sunset. All's relative. The sense of perspective and point of reference. Most of all: the limits that define us: the breadth of our breath and the width of our brow. All our stories and all our beliefs. Our laws, our traditions, our ideas of love, of economics, of mine, of yours. We create systems and structures that define us and tell us how to live in community with others. All of those systems: imagined ideas, dependent on each other and, most of all, on the belief in the solidity and actuality of this 'I'. I am this. I am not that. I have this. I do not have that. Where am I in this picture? Where do I fit? And does it translate to YOU?

Every image has a perspective and offers a glimpse of what-i-see-from-here. There can be so much to a little sky scape on a little canvas. And, then again, nothing at all. Paint, arranged in a specific array, that evokes a sensation. And a flurry of ideas.

A Reason for Art

Why do we value art?

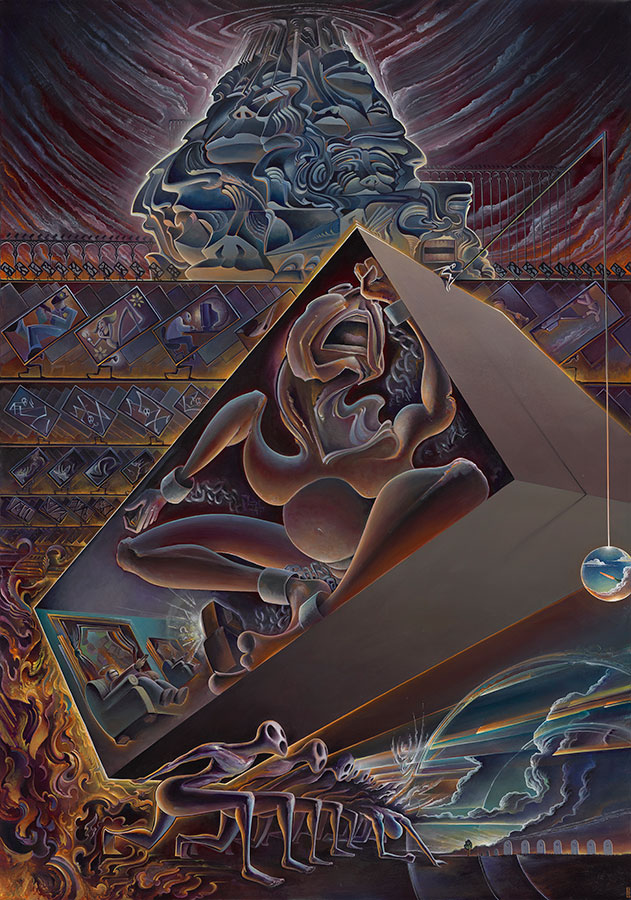

Art: it's this visual record of who we are, how we imagine ourselves, where we're going, where we've come from at some particular time. It's the visual record of out psycho-spiritual states - as a human organism. If you were to take all the varied pieces of art from all the different art movements in some brief span of time, you'd find a vast spectrum of emotions, perspectives, and inspirations. Yet, it all came from the same place - this Earth, these humans - and happened within the same relative time.

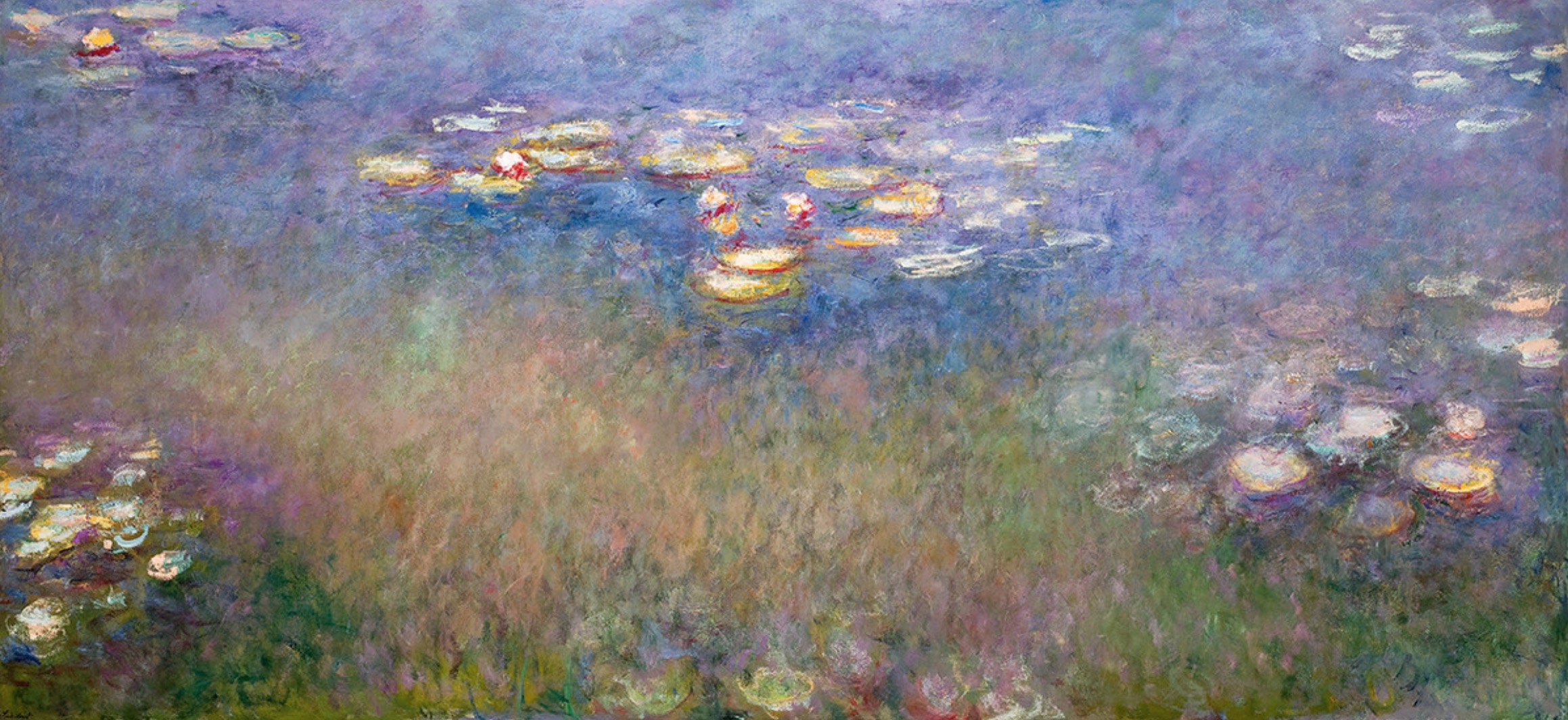

Monet, His Waterlilies, and the Creative Drive

“Yesterday I resumed work. It’s the best way to avoid thinking of these sad times. All the same, I feel ashamed to think about my little researches into form and colour while so many people are suffering and dying...”

- Claude Monet - 1914 (While working on his water lilies paintings during World War I.)

From: Wartime water lilies: how Monet created his garden at Giverny

I feel like this sometimes. There's so much going on. There's this endless stream of chaos beating down my door. Who am I to turn my back on this issue or that issue and "resume my little researches into form and colour" while so much pain and suffering exists. Maybe it's the fact that joy CAN exist side by side with the pain.

Dear Artist

Dear Artist,

Often, when asked what advice I might give to you, I say something like, “Practice!” Or, “Do it every day!” Or some such thing. Everyone says it and it's true. But the deeper truth is - all of that is meaningless if not for one thing. There is only one real insight I can offer you:

YOU HAVE TO LOVE IT.

Why Art is Expensive :or: Pricing Your Art So You Can Live

First, I will say what this post is not. This is not about what gives art value. I've written other pieces about that and probably will again. Nor is this about, say, why a David Hockney painting sold for $90.3 million. That isn't a question of 'why is art expensive' but 'why is it SO expensive' and that question has also been discussed elsewhere.

Instead, we're simply going to talk about the cost of a work of art as an equation of what goes into it, what one (in this case, the artist) should reasonably expect to get out of it, and how that creates the space for further explorations.

How to Be a Painter I

Look: you have to have complete understanding of when your hand is heavy handed, and when it is light. What that feels like, and how to hold the brush. Sometimes though you need to be heavy handed and sometimes light and you need to know that too. How to be able to hold the brush so lightly that, any lighter, and you would drop it. How to hold the brush firmly and yet, still allow it to have give - to feel the push and pull of the canvas on the brush as much as the hand that seeks to drive it.

You should know how to dip your brush in the water so only a millimeter of it’s tip is submerged but pull it out quick so it only has one drop of water on it. If it has two, you will know before your brush even touches the canvas, so flick it aside with just the quickest and limberest flicks of the wrist, and the extra drop of water will fly away and not defile your painting and create a headache and drip down below you onto that perfectly and profoundly finished sky. And you must be able to do that in a split second because, thought you need a touch more water, you have no time to look away from the painting because it is all happening there. The flower pot is becoming, the sky is opening, the waters are parting… the god of all of your gods is arriving and you can’t miss it for a second.