I’d like to share an excerpt from “Concerning the Spiritual in Art” by Wassily Kandinsky, published in 1914. I feelfound that his visual representation of the job of the artist, as he describes it, is particularly helpful when I try to understand my place in this world as an artist. Kandinsky, who might seem a bit antiquated today, was a visionary in his own right. As an artist, he methodically focused his internal lens to paint what came up in a semi-logical and abstract manner. As a writer and thinker, he was looking to understand just what it is that makes up art if it isn’t to be a reproduction of the physical world or a regurgitation of spiritual/mythical symbolism.

I’ve heard people say: but his work is just lines, circles, and weird mish-mashes of color. Think of his work as the first few steps into (or out of) the lucid imagination. His work is part of those early tentative steps into the creative sub/unconscious – into the whole of the inner world. This was a new thing, a new experience, at the time- this painting what you feel instead of what you see, think, or believe. Those first tentative muddlings that grew into precise diagrammatic explorations with a host of attendant essays and diagrams helped to lay the ground work for the hosts of art movements and internal explorations that came after, giving free reign (as we do now) to our collective human creative explorations.

Those early steps may seem wobbly and unsure at times – like a child who has just taken their first steps. Yet, the sense of triumph – the sense of really getting somewhere – is unmistakable. Few had done this before his time. He and his contemporaries were, I believe, some of the first pioneers into the world of translating the internal mental landscape, using art as a method of digging deeper and further into the mind-heart space. What they found there is of value to everyone. It is what makes his art timeless and a necessary piece of the story that is Modern Art.

Now, onto “Concerning the Spiritual in Art”…

{from Part I/Chapter II: The Movement of the Triangle}

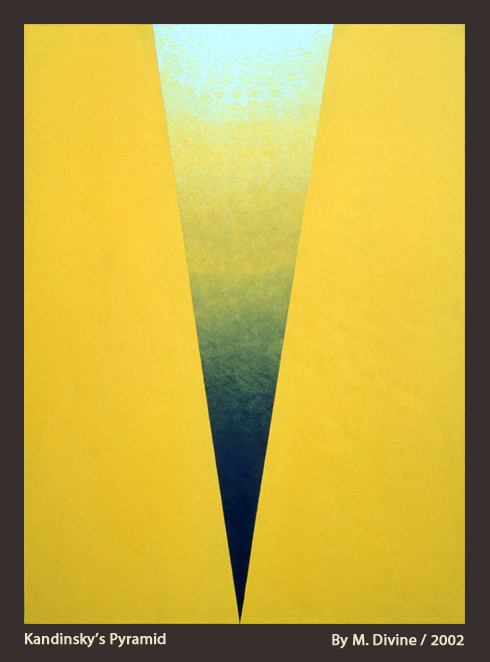

The life of the spirit may be fairly represented in diagram as a large acute-angled triangle divided horizontally into unequal parts with the narrowest segment uppermost. The lower the segment the greater it is in breadth, depth, and area.

The whole triangle is moving slowly, almost invisibly forwards and upwards. Where the apex was today the second segment is tomorrow; what today can be understood only by the apex and to the rest of the triangle is an incomprehensible gibberish, forms tomorrow the true thought and feeling of the second segment.

At the apex of the top segment stands often one man, and only one. His joyful vision cloaks a vast sorrow. Even those who are nearest to him in sympathy do not understand him. Angrily they abuse him as charlatan or madman. So in his lifetime stood Beethoven, solitary and insulted.

[My note: so Kandinsky is a tad sexist here: ‘one man’ – let’s just give him the benefit of the doubt that, really, he meant more than man, more than woman. he meant any visionary]

How many years will it be before a greater segment of the triangle reaches the spot where [w]e once stood alone? Despite memorials and statues, are they really many who have risen to his level?

In every segment of the triangle are artists. Each one of them who can see beyond the limits of his segment is a prophet to those about him, and helps the advance of the obstinate whole. But those who are blind, or those who retard the movement of the triangle for baser reasons, are fully understood by their fellows and acclaimed for their genius. The greater the segment (which is the same as saying the lower it lies in the triangle) so the greater the number who understand the words of the artist. Every segment hungers consciously or, much more often, unconsciously for their corresponding spiritual food. This food is offered by the artists, and for this food the segment immediately below will tomorrow be stretching out eager hands.

This simile of the triangle cannot be said to express every aspect of the spiritual life. For instance, there is never an absolute shadow-side to the picture, never a piece of unrelieved gloom. Even too often it happens that one level of spiritual food suffices for the nourishment of those who are already in a higher segment. But for them this food is poison; in small quantities it depresses their souls gradually into a lower segment; in large quantities it hurls them suddenly into the depths ever lower and lower. Sienkiewicz, in one of his novels, compares the spiritual life to swimming; for the man who does not strive tirelessly, who does not fight continually against sinking, will mentally and morally go under. In this strait a man’s talent (again in the biblical sense) becomes a curse–and not only the talent of the artist, but also of those who eat this poisoned food. The artist uses his strength to flatter his lower needs; in an ostensibly artistic form he presents what is impure, draws the weaker elements to him, mixes them with evil, betrays men and helps them to betray themselves, while they convince themselves and others that they are spiritually thirsty, and that from this pure spring they may quench their thirst. Such art does not help the forward movement, but hinders it, dragging back those who are striving to press onward, and spreading pestilence abroad.

Such periods, during which art has no noble champion, during which the true spiritual food is wanting, are periods of retrogression in the spiritual world. Ceaselessly souls fall from the higher to the lower segments of the triangle, and the whole seems motionless, or even to move down and backwards. Men attribute to these blind and dumb periods a special value, for they judge them by outward results, thinking only of material well-being. They hail some technical advance, which can help nothing but the body, as a great achievement. Real spiritual gains are at best under-valued, at worst entirely ignored.

The solitary visionaries are despised or regarded as abnormal and eccentric. Those who are not wrapped in lethargy and who feel vague longings for spiritual life and knowledge and progress, cry in harsh chorus, without any to comfort them. The night of the spirit falls more and more darkly. Deeper becomes the misery of these blind and terrified guides, and their followers, tormented and unnerved by fear and doubt, prefer to this gradual darkening the final sudden leap into the blackness.

At such a time art ministers to lower needs, and is used for material ends. She seeks her substance in hard realities because she knows of nothing nobler. Objects, the reproduction of which is considered her sole aim, remain monotonously the same. The question “what?” disappears from art; only the question “how?” remains. By what method are these material objects to be reproduced? The word becomes a creed. Art has lost her soul. In the search for method the artist goes still further. Art becomes so specialized as to be comprehensible only to artists, and they complain bitterly of public indifference to their work. For since the artist in such times has no need to say much, but only to be notorious for some small originality and consequently lauded by a small group of patrons and connoisseurs (which incidentally is also a very profitable business for him), there arise a crowd of gifted and skilful painters, so easy does the conquest of art appear. In each artistic circle are thousands of such artists, of whom the majority seek only for some new technical manner, and who produce millions of works of art without enthusiasm, with cold hearts and souls asleep.

Competition arises. The wild battle for success becomes more and more material. Small groups who have fought their way to the top of the chaotic world of art and picture-making entrench themselves in the territory they have won. The public, left far behind, looks on bewildered, loses interest and turns away.

But despite all this confusion, this chaos, this wild hunt for notoriety, the spiritual triangle, slowly but surely, with irresistible strength, moves onwards and upwards.

The invisible Moses descends from the mountain and sees the dance round the golden calf. But he brings with him fresh stores of wisdom to man.

First by the artist is heard his voice, the voice that is inaudible to the crowd. Almost unknowingly the artist follows the call. Already in that very question “how?” lies a hidden seed of renaissance. For when this “how?” remains without any fruitful answer, there is always a possibility that the same “something” (which we call personality today) may be able to see in the objects about it not only what is purely material but also something less solid; something less “bodily” than was seen in the period of realism, when the universal aim was to reproduce anything “as it really is” and without fantastic imagination.

If the emotional power of the artist can overwhelm the “how?” and can give free scope to his finer feelings, then art is on the crest of the road by which she will not fail later on to find the “what” she has lost, the “what” which will show the way to the spiritual food of the newly awakened spiritual life. This “what?” will no longer be the material, objective “what” of the former period, but the internal truth of art, the soul without which the body (i.e. the “how”) can never be healthy, whether in an individual or in a whole people.

THIS “WHAT” IS THE INTERNAL TRUTH WHICH ONLY ART CAN DIVINE, WHICH ONLY ART CAN EXPRESS BY THOSE MEANS OF EXPRESSION WHICH ARE HERS ALONE.

You can read the entire book (which is fairly short) here: http://www.mnstate.edu/gracyk/courses/phil%20of%20art/kandinskytext.htm or find it anywhere from Amazon to eBay to many an independent book store.